Author of Gold King Mine spill book will speak in Shiprock

Jonathan Thompson part of panel discussion at Tuesday event

- "Sharing Stories Across the Watershed" begins at 6 p.m. Tuesday at the Shiprock Chapter house.

- Thompson has years of experience as an environmental reporter at newspapers in southwest Colorado.

- His family history in the area extends back to the 1870s.

FARMINGTON — Jonathan Thompson already had years of experience as an environmental reporter in southwest Colorado when the Gold King Mine spill took place almost three years ago. So he acknowledges he was more than a little jaded about the idea of environmental disasters and was dismissive about the significance of the Aug. 5, 2015, spill when the first news reports about it emerged.

"To be honest, when the spill first happened and there was this frenzy about it, my editors at the High Country News (the newspaper Thompson worked for at the time) called me, saying, 'We have to get on this.' My response was, 'We've got bigger fish to fry. I've heard this before, and it's not as big a deal as you think.' I wasn't crazy about writing about it."

He quickly changed his opinion when he saw the river a few hours later at a crossing north of Durango, Colorado. Thompson recalls going to the riverbank and sticking his hand into the sickly orange water that a few hours later had been its usual sparkling green.

"Holy crap!" he said to himself, realizing he couldn't see his hand 3 inches underwater.

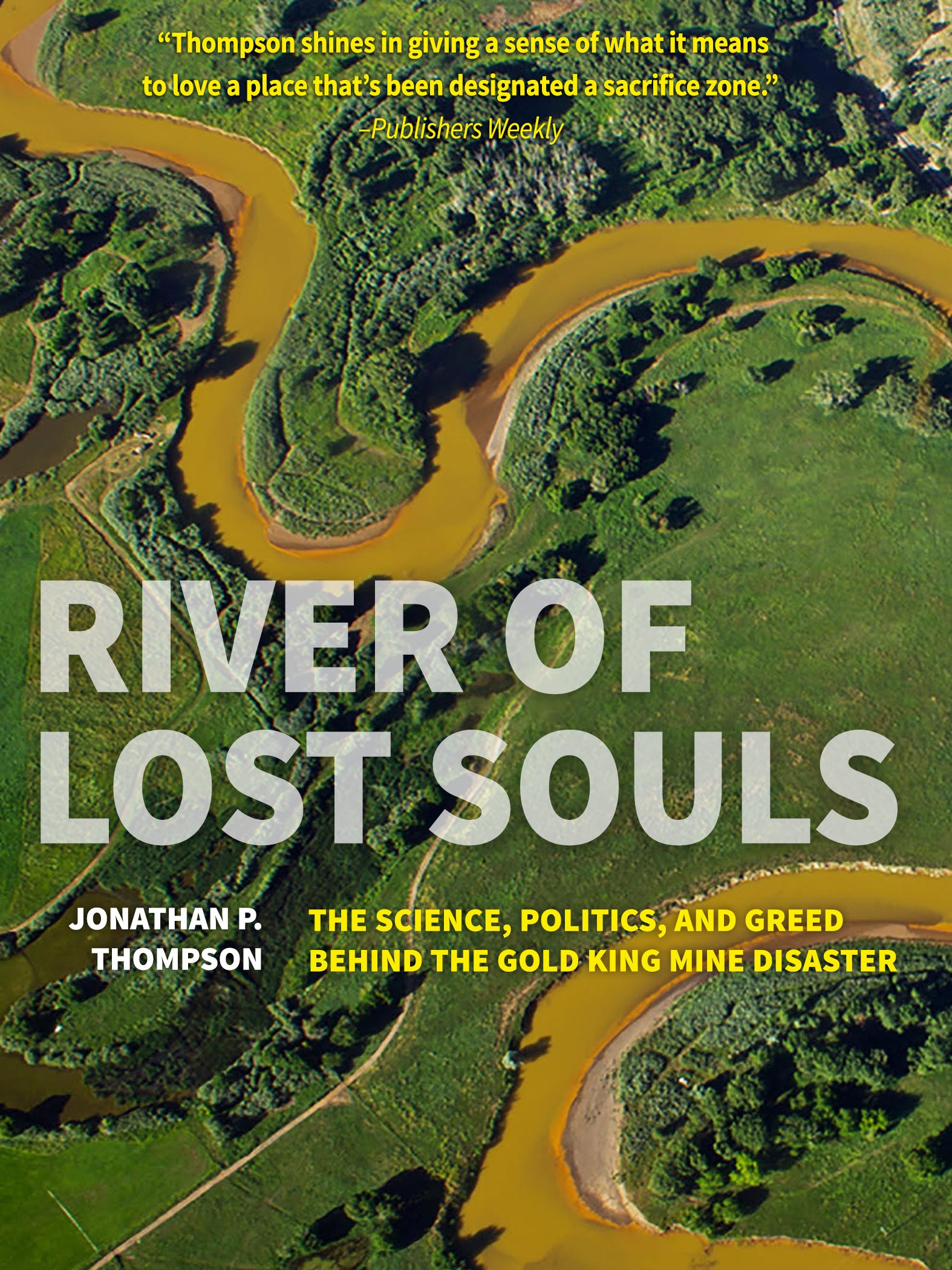

The visceral impact of that first look at the Animas River in the aftermath of the spill remains with him to this day. It was the first step in a process that ultimately led him not just to cover the story extensively, but to write an exhaustive account of the spill, "River of Lost Souls," a book published by the Salt Lake City-based Torrey House Press, that was released earlier this month.

Thompson will be part of a panel discussion during the "Sharing Stories Across the Watershed" event at 6 p.m. Tuesday at the Shiprock Chapter house in Shiprock. Thompson will be joined by three other panel members who will be sharing their perspectives on Animas-San Juan rivers system and the spill's impact on downstream communities.

"My perspective changed from 'This isn't a very big deal,'" Thompson said during a phone interview Friday while driving through western Colorado on his way to a book signing and reading in Denver. "The more time that passes and the more this stays on people's minds, the more of a big deal it seems to me."

The spill wound up dumping 880,000 pounds of heavy metals into Cement Creek, which flows into the Animas River and then the San Juan River. The disaster had serious implications for downstream communities for hundreds of miles in terms of drinking water quality, agricultural irrigation and soil contamination.

More:EPA adds Gold King Mine to list of Superfund site

Thompson addresses those issues thoroughly, but his book attempts to put the events of August 2015 in a historical context that he believes few people understand well. "River of Lost Souls" covers the entire history of human settlement in the Animas River watershed, illustrating how the relationship between people and the river has evolved over time.

The author's family roots in southwest Colorado go back to the 1870s, so his personal history, as well as his experience as an environmental reporter, both played an important role in his writing process.

Thompson said he originally planned to write "River of Lost Souls" in a more traditional, third-person style, although it was clear to him from the beginning there would need to be a fair amount of first-person narrative. But it is clear from just the first few pages that "River of Lost Souls" is a deeply personal story to Thompson, perhaps even serving as something of a cathartic experience.

"My time as a newspaper guy in Silverton was integral to the story … When I first thought of (the book), I didn't know I would get into my personal history so much. That came out of it as I went along.

"My goal was to give context (to the spill). There was so much coverage it, as is the nature of news," Thompson said, explaining his approach to writing the book. "But I realized it didn't have much context. As I was writing about it, I realized my family was there and was a part of it. I think pulling that in there makes it more real and easier to get into."

Though he already was well versed in the history of the watershed and mining issues when the spill happened, one aspect of the story was new to Thompson.

More:Officials mark anniversary of Gold King Mine spill

"The most surprising thing to me was learning about the long history of resistance to mining pollution," he said. "There was an uprising against it in 1880."

Like many people, Thompson said he had assumed that significant protests against environmental degradation had been around only since the late 1960s and early 1970s. But his research uncovered several instances of farmers and ranchers in the Animas Valley registering their displeasure with the negative impact of mining on the river dating back to the late 19th century — some of it quite heated, he said.

"It makes a lot of today's environmental resistance look tame," he said.

Since they relied on the Animas River for their livelihood, many of those farmers and ranchers were protecting their own economic interests by complaining about such mining company practices as dumping tailings directly into the waterway, Thompson said. But he also found evidence that their concerns were more than one dimensional.

"A lot of it was pure environmentalism," he said. "It shocked and disturbed them to see the river degraded and fish getting killed."

More:EPA says it won't pay $1.2B in mine spill claims

Considering how many waste-filled abandoned mines remain in the mountains of southwest Colorado, Thompson said it's difficult for him to be hopeful that another disastrous spill won't take place.

"There's no fix for it," he said. "You can't go in and scoop up the waste and bury it somewhere and call it good. That's not the way it works. You can only manage it with water treatment plants that go on forever.

"That's not to say nothing can be done," he continued. "There's lots of room for experimentation, and the optimistic side of me says maybe Silverton can become a laboratory for water-cleaning techniques and methods. That would also help the economy up there, which desperately needs it. I try to be optimistic."

Mike Easterling is the night editor of The Daily Times. He can be reached at 505-564-4610.